If you get easily annoyed or lose your temper it may not be anger. Shame is a painful, visceral emotion, that may lurk behind. But what can you do about anger when it is a cover for shame?

Anger in the pandemic

We are living in the strangest time in living history. The coronavirus pandemic has required that we all make changes. And this situation and the virus may have affected us in many other ways.

We are in forced confinement with our spouse, partner or even our kids, that may be too close for comfort. Our usual coping strategies, of travel, socialising etc may have been taken away from us. We are in a situation where we are more isolated, even in the safety of our own home.

What can we do about anger?

If you find yourself shouting more, getting irate on the phone, barely able to hide your annoyance at that stranger who passed you a little too close in the street, or full of rage of the increase in footfall on your usual walking routes. Perhaps you have become meaner. For many of us, anger is easier to do than what may be lurking beneath: shame.

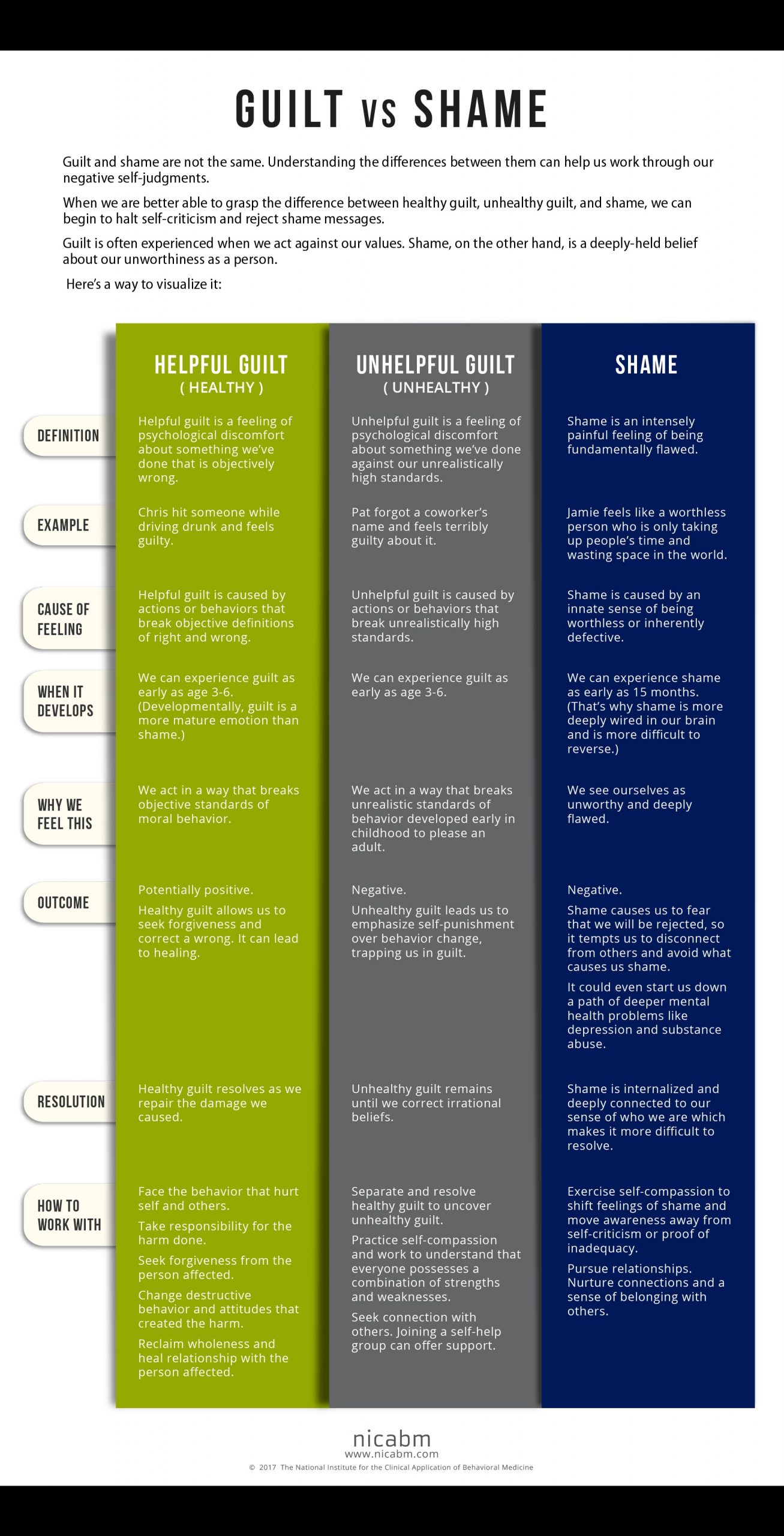

Shame is a difficult emotion and perhaps one of the last taboos in our society. Shame is an acutely painful feeling of feeling fundamentally wrong or inadequate. A deeply held belief about our unworthiness or lack of ‘goodness’ as a person.

We cover it up

In fact, it can be an incredibly painful experience, especially when there are layers of shame that have built up over the years. And if we were shamed or humiliated as a child, intentionally or otherwise, and it wasn’t contained or seen. If we carry these layers of shame into our adult life, and a situation or event, often in relationships, triggers it we can have a strong physiological reaction. It can feel like a weight or dread in our stomach, we may feel nauseous or actually be sick, or faint. We might tremble, or feel dizzy. All said, shame wants to make us hide, to disappear.

Of course, something as terrible as this often cannot be tolerated. So we do something else instead. Often that involves us getting angry.

This might come out as bursts of irritability or even rage: at our loved ones, or at strangers. Though loved ones are often ‘safer’ so they may get the brunt of it. And then we feel terrible. This increases the shame experience and propagates the cycle of shame.

Where else the anger might appear

Another way that anger comes out, perhaps in a more passive-aggressive or certainly indirect way, is through blame. We project the shame onto others and blame them. We split the world into ‘goodies’ and ‘baddies’ and, for the slightest perceived indiscretion, the other becomes all bad. So we turn against family and friends. People around us cannot tolerate this unfair treatment. So we become more isolated. And our shame is triggered.

The purpose of shame

Guilt is a sense that ‘I have done something wrong’ rather than the ‘I am wrong’ of shame. Both, believe it or not, are prosocial emotions in that they have a healthy purpose in humans. Shame is there as an indicator that we have done or said something, or behaved in some way, that may cause us to risk our position in our group, family or society as a whole. So this terrible feeling, acts as an impetus for us to change and therefore belong. It is prosocial in that it increases our connectedness to others.

Origins of shame

We can experience shame very early in life, in pre-verbal stages in fact. As early as 15 months, an infant can have a visceral experience of being defective. Perhaps if a mother is unresponsive, neglectful or intrusive. The pre-verbal origins might explain why the visceral quality, the felt experience, of shame is do debilitating. The posture of collapse that shame brings about, initiates a similar collapse in our nervous system: vagal syncope. We go into freeze mode or disconnection and dissociation. All this happens outside of our conscious awareness, precisely because of the pre-verbal, beyond words and thought, origins of shame.

Causes and sources of shame

Causes of shame are multitudinous and happen at all ages and stages of life. Some examples might be: our body or our bodily functions; sex and sexuality; relationships; achievements or lack of achievement. Parental rejection is a certain source of shame but so are high expectations or punishment. These experiences of punishing external figures can be internalised as a bad object that continues to punish and shame us, in a self-propagating way, for the rest of our lives. And shame is massively linked to trauma of all types. Trauma and the fear of being shamed can lead to the ‘vagal syncope’ that Peter Levine talks about where our body and our mind shut down.

Secrecy and isolation

Shame multiplies with secrecy, isolation, and judgement. But it also demands us to keep quiet. But if we can be brave enough to talk about our shame with a caring other, we can start to shed its despotic layers. Shame often gets caught up with other, positive or negative, emotions. This might be desire, or pleasure; fear or anger; pride or sadness. Perhaps this is when shame becomes particularly toxic. Think about the young woman in whom shame has become bound with pleasure, who experiences overwhelming negative states in love making with her husband. Or the young man who is not able to experience any pride in what he does becomes shame is linked with it.

What can you do about anger linked with shame

Whilst anger often presents instead of shame, anger can also be bound with shame. If our early sources of shame involve anger, ours or others, the vicious cycle will be compounded when we experience anger as a defence against shame. You can probably imagine how toxic and debilitating this experience can be for someone. Caught in a cycle of explosive outbursts beyond their control and then overwhelmed into shutdown by those outbursts.

Here are some important things to consider to break the cycle of shame:

- Understand the complex nature of shame – it is an emotion that is at the heart of trauma and causes more trauma. It is internalised and often self-propagating and there may be layers of it. Its causes can also be trans-generational – shame in families that has not directly impacted us, can be passed on and internalised.

- Talk – shame thrives on silence and secrecy. But also judgement. So it is important to find an empathetic, non-judgemental other to whom you can tell your story.

- Healthy pride – it is said that the internal extinguisher for the fire of shame is healthy pride. We often, in our culture, have an unhealthy relationship with pride. But healthy pride – being able to celebrate and recognised our qualities, successes and achievements – is a powerful antidote to shame.

- Posture – unconsciously, in small or significant ways, when our shame is triggered, we adopt a certain posture that kind of sucks us deeper into shame. This posture is closed and collapsed and our head and eyes are downwards. By changing our posture and keeping upright with an open chest and eyes looking upwards, we can take at least some control.

- Breathing and HRV – shame throws us into chaos. This is a state of physiological incoherence. By learning breathing techniques to increase our heart rate variability, and coherence, we can begin to break the debilitating cycle of shame.

- Seek therapy – for all of the above reasons, therapy can be a useful resource to deal with shame.

Here is a useful infographic that explains shame in relation to guilt.